About the first of October, I went to some garage and estate sales and one antique sale to see if something might jump out at me. At the antique sale--the advertisement in the paper was under "Antiques" instead of "Garage Sales"--was a collection of old pewter and a model ship hull with a tangle of string and pieces of what had been masts and yardarms. The lady tending the sale told me that the ship was ivory and had belonged to her mother. She was reducing the amount of her stuff, and had asked her son if he wanted anything. He wanted the ship, and as she lifted it from the mantel, she dropped it. It shattered.

Now her son did not want it, so she was selling the remains. She assured me that all the pieces were there. I doubted it: shattered masts, broken yardarms, minuscule beads, lines so fragile they disintegrated at a touch. I took the collection home to study, and decided that I needed to remove the lines, start from scratch. I did not think to take a photo until after I had cleared most of the lines, I'm sorry to say. I started trying to figure out how the pieces fit together and how to fix them Regular glue did not hold, super glue failed; finally at a bead store I stumbled on "Crafter's Pick," a multi-purpose glue that worked.

I put the masts together and fit them and found that my problems were just beginning. I spent hours searching the Internet to find directions for rigging square riggers.

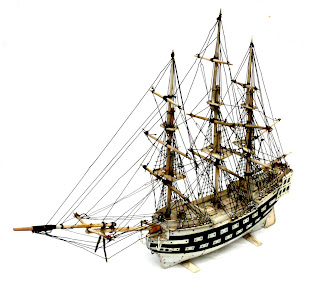

Along the way, I discovered that the model was probably not ivory at all but bone and baleen, similar to models made in the early 1800s by French prisoners in the long wars between England and France, models now sold at Christie's and Sotheby's. Using the remains of the rigging and patterns from the Internet, I managed a facsimile of an 18th century three-masted square rigger with 32 guns on two decks.

The lines are silk thread ranging from .35 mm for foot lines to .60 mm for shrouds. The main mast is just over 12 inches above the keel, the hull is about 9 inches long by 3 inches at the beam.

In all, I spent some 50 hours stringing lines, I have no idea how much time I spent traveling the net looking for answers.

Now her son did not want it, so she was selling the remains. She assured me that all the pieces were there. I doubted it: shattered masts, broken yardarms, minuscule beads, lines so fragile they disintegrated at a touch. I took the collection home to study, and decided that I needed to remove the lines, start from scratch. I did not think to take a photo until after I had cleared most of the lines, I'm sorry to say. I started trying to figure out how the pieces fit together and how to fix them Regular glue did not hold, super glue failed; finally at a bead store I stumbled on "Crafter's Pick," a multi-purpose glue that worked.

I put the masts together and fit them and found that my problems were just beginning. I spent hours searching the Internet to find directions for rigging square riggers.

Along the way, I discovered that the model was probably not ivory at all but bone and baleen, similar to models made in the early 1800s by French prisoners in the long wars between England and France, models now sold at Christie's and Sotheby's. Using the remains of the rigging and patterns from the Internet, I managed a facsimile of an 18th century three-masted square rigger with 32 guns on two decks.

The lines are silk thread ranging from .35 mm for foot lines to .60 mm for shrouds. The main mast is just over 12 inches above the keel, the hull is about 9 inches long by 3 inches at the beam.

In all, I spent some 50 hours stringing lines, I have no idea how much time I spent traveling the net looking for answers.

No comments:

Post a Comment